Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month 2021

Where does the term “Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI)” come from? Who is included, and what does it stand for?

The term “Asian American” was first coined by two students at Berkeley in the late 1960s when they organized the Asian American Political Alliance. Inspired by the Black Power movement, they developed the term to unite students from diverse Asian backgrounds to fight in solidarity against U.S. racial discrimination and imperialism.

In the 1980s, the U.S. Census expanded the definition of “Asian American” to encompass people of Pacific Islander descent, though in the late 1990s/early 2000s, it disaggregated “Native Hawaiian” and “Pacific Islander” as distinct categories under the Asian American umbrella. Today the term is often applied broadly to people of Asian, Asian American, or Pacific Islander ancestry—often to the detriment of many communities.

In the 1980s, the U.S. Census expanded the definition of “Asian American” to encompass people of Pacific Islander descent, though in the late 1990s/early 2000s, it disaggregated “Native Hawaiian” and “Pacific Islander” as distinct categories under the Asian American umbrella. Today the term is often applied broadly to people of Asian, Asian American, or Pacific Islander ancestry—often to the detriment of many communities.

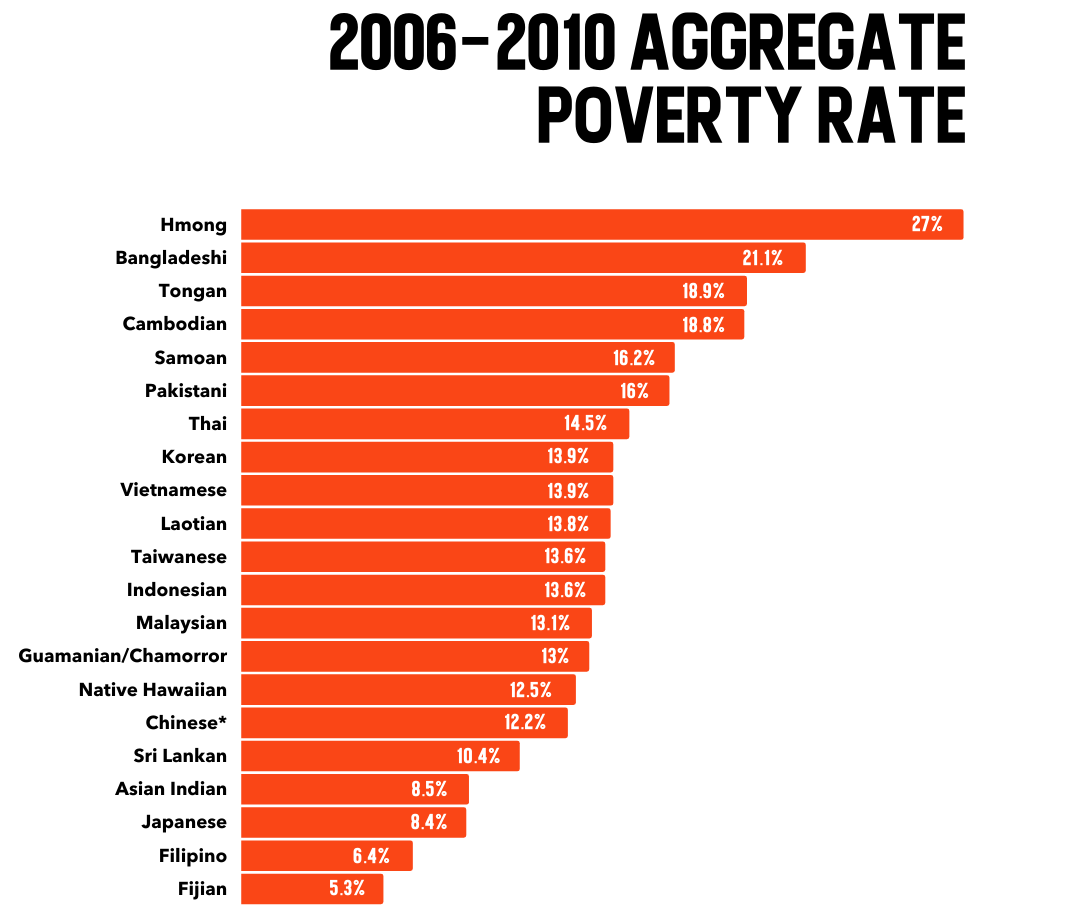

While the term was initially created in an effort to fuel solidarity movements, it has grown to comprise more than 50 different racial and ethnic categories, thereby obscuring disparate experiences and inequities that exist among the groups. The subgrouping of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) groups is particularly problematic, for it fails to account for vast social and economic discrepancies stemming from histories of settler colonialism and institutionalized racism.

Because the term Asian American tends to center people of East Asian racial and ethnic descent (who themselves are composed of multiple ethnicities and experiences, including histories of inter-Asian colonial occupation), policies aimed at addressing issues of Asian Americans as a monolith continue to erase, marginalize, silence, and withhold resources for many groups subsumed under that moniker. In particular, the continued pervasiveness of the “Model Minority Myth”—a pernicious stereotype specifically deployed to weaponize Asian Americans against Black Americans—hides the realities that Asians in the U.S. have the largest income gap of any racial group; the lowest rates of homeownership; and continue to experience significant disparities in education attainment and healthcare outcomes.

Because the term Asian American tends to center people of East Asian racial and ethnic descent (who themselves are composed of multiple ethnicities and experiences, including histories of inter-Asian colonial occupation), policies aimed at addressing issues of Asian Americans as a monolith continue to erase, marginalize, silence, and withhold resources for many groups subsumed under that moniker. In particular, the continued pervasiveness of the “Model Minority Myth”—a pernicious stereotype specifically deployed to weaponize Asian Americans against Black Americans—hides the realities that Asians in the U.S. have the largest income gap of any racial group; the lowest rates of homeownership; and continue to experience significant disparities in education attainment and healthcare outcomes.

YURI KOCHIYAMA

YURI KOCHIYAMA

Yuri Kochiyama is a civil rights activist who worked in close alliance with Malcom X and the Organization for Afro-American Unity, the Young Lords, and the Harlem Community for Self-Defense—just to name a few.

As a survivor of Japanese concentration camps organized by the U.S. during WWII to wrongfully imprison over 120,000 Japanese/Japanese Americans, Kochiyama founded Asian Americans for Action, a political group allied with Black Liberation efforts, and fought tirelessly for redress and reparations for Japanese and Black Americans. She held frequent salons in her apartment on 125th Street in Harlem, a place which came to be called, “Grand Central Station,” and “The Revolutionary Salon.” On any given night, she and her partner Bill could be found hosting—among others—Malcolm X and his family, Puerto Rican nationalists, coalition members organizing for justice for Vincent Chin, and Tupac, who at nine years old, addressed a group in her living room on the need to free political prisoners.

As instances of anti-Asian violence continue to circulate in the media, many of which appear to feature perpetrators who are Black, it is critical to acknowledge that the majority of anti-Asian hate crimes are committed by White people and that White Christian nationalism is one of the most significant predictors of anti-Asian xenophobia. Such biased media attention only serves to exacerbate anti-Black sentiment in Asian communities; perpetuate tropes of Black-Asian conflict; harm Black communities and other communities of color with increased policing—a system unambiguously rooted in anti-Blackness and White supremacist racism—and avoid addressing the larger problems of xenophobia and exclusion which give space for anti-Asian violence to arise in the first place.

Figures like Yuri Kochiyama remind us that multi-racial, multi-ethnic solidarity not only exists but is integral to the work of dismantling racism. As she notes herself, “My priority would be to fight against polarization. Because this whole society is so polarized. I think there are so many issues that all people of color should come together on, and there are forces in this country who want this polarization to take place.”

MORE ON YURI KOCHIYAMA